500-Year-Old Printing Error Revolutionized Geography

Precisely five centuries ago, a printing mishap in a Bible featuring an inverted map of the Holy Land ignited profound shifts in perceptions of geography, territorial boundaries, and the very concept of nationhood. Even with this significant mistake, the map fundamentally altered the Bible, transforming it into a hallmark of the Renaissance era. It disseminated innovative concepts regarding territorial structuring amid rising literacy rates. Gradually, what began as sacred cartography transitioned into the foundation for delineating political frontiers, profoundly impacting early modern intellectual currents as well as contemporary views on sovereign states.

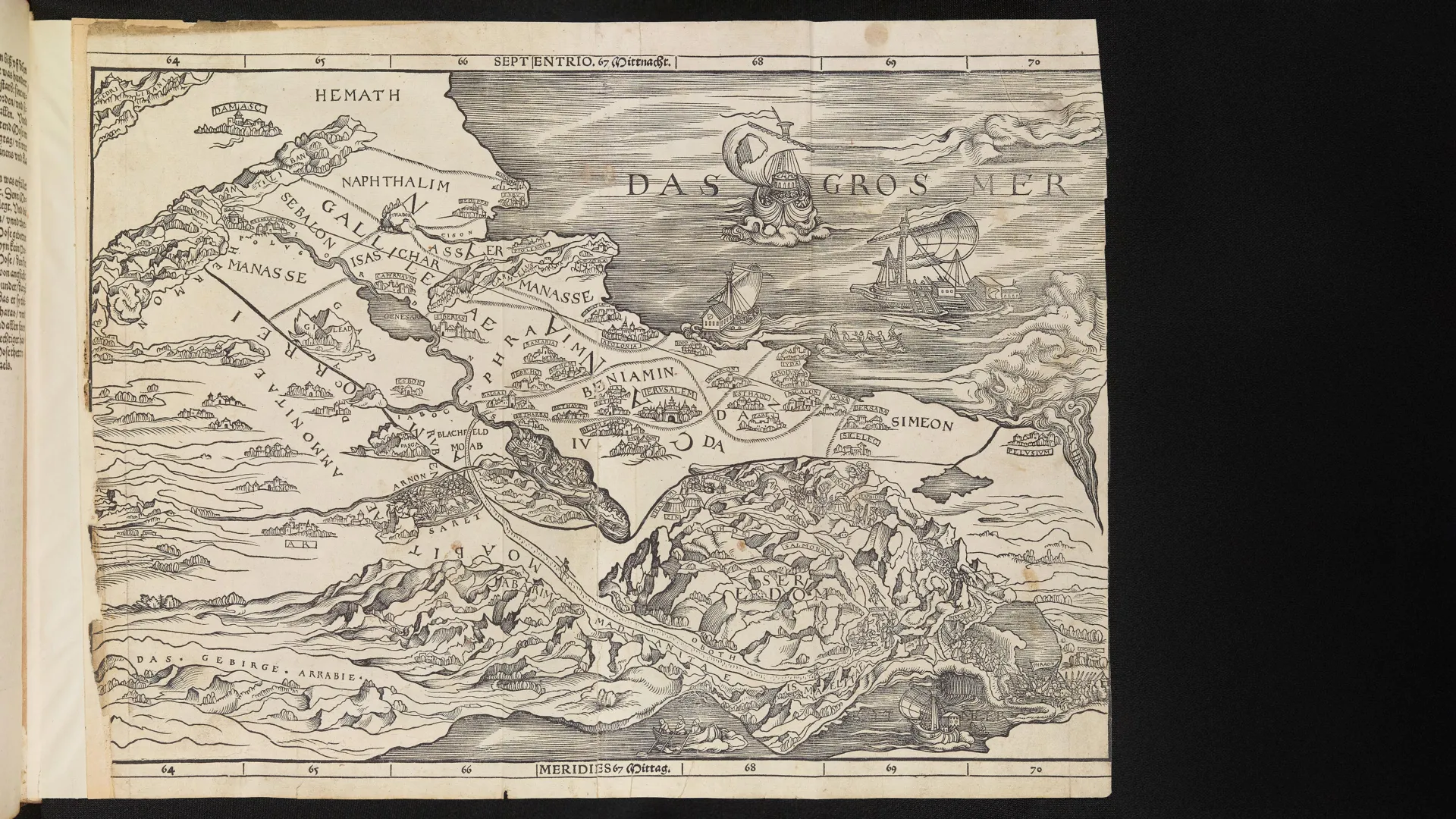

The inaugural Bible incorporating a map of the Holy Land emerged in 1525, marking exactly 500 years ago. This map suffered from a critical defect: it was oriented incorrectly, depicting the Mediterranean Sea positioned to the east. Nevertheless, a recent study from the University of Cambridge reveals that its inclusion in printed form propelled forward-thinking notions about territory and boundaries that continue to resonate in present-day discourse.

“This event stands as both one of the most notable setbacks and resounding successes in the annals of publishing,” states Nathan MacDonald, Professor of the Interpretation of the Old Testament at the University of Cambridge.

“The map was inadvertently printed in reverse, placing the Mediterranean to the east of Palestine. Europeans possessed such scant knowledge of that region that apparently no one in the print shop detected the issue. Yet, this very map forever altered the Bible, and nowadays, the majority of Bibles feature maps.”

Renaissance Cartography Redefined Biblical Presentation

In a study released on November 29 in The Journal of Theological Studies, MacDonald contends that the map, crafted by Lucas Cranach the Elder and produced in Zürich, extended beyond mere aesthetic updates to biblical formatting for the Renaissance period. It played a pivotal role in molding nascent ideas on territorial arrangements.

“It has long been mistakenly believed that biblical maps merely reflected an emerging early modern propensity for charts with distinctly outlined territorial segments,” MacDonald explains. “In truth, these Holy Land maps spearheaded that transformation.

“As Bible accessibility proliferated from the 17th century onward, these maps propagated visions of ideal global organization and individuals’ positions therein. This influence persists powerfully to this day.”

Scarce Remaining Copies from the 1525 Print Run

Only a handful of copies from Christopher Froschauer’s 1525 Old Testament edition survive today. One such precious artifact resides in Trinity College Cambridge’s Wren Library.

Within this volume, Cranach’s map delineates the Israelites’ wilderness journey stations alongside the allocation of the Promised Land among the twelve tribes. This portrayal embodied a uniquely Christian perspective, asserting claims over sacred locales from both Testaments. Cranach’s design echoed medieval cartographic conventions, rendering Israel as elongated, slender land strips—a simplification derived from the 1st-century Jewish historian Josephus, who reconciled disparate biblical accounts.

MacDonald observes, “The biblical passages in Joshua 13-19 fail to provide a fully unified depiction of tribal lands and cities. Multiple inconsistencies arise. The map assisted readers in comprehending the narrative, despite its geographical imprecisions.”

Cartography’s Role Amid the Swiss Reformation

A strict, literal scriptural exegesis held paramount importance during the Swiss Reformation, which accounts for why, as MacDonald notes, “It comes as no surprise that the pioneering Bible map originated in Zürich.”

A Fellow of St John’s College Cambridge, MacDonald highlights how surging interest in literal interpretations elevated maps as instruments demonstrating that biblical occurrences transpired in tangible locations and historical timelines.

In the Reformation milieu, where select religious imagery faced prohibitions, Holy Land maps emerged as permissible visual supports, acquiring devotional weight.

“Gazing upon Cranach’s map—lingering at Mount Carmel, Nazareth, the River Jordan, and Jericho—viewers embarked on an imagined pilgrimage,” MacDonald describes. “Mentally traversing the terrain, they relived the sacred narratives.”

A Pivotal Milestone in Biblical Evolution

MacDonald posits that incorporating Cranach’s map constituted a landmark in the Bible’s ongoing metamorphosis, meriting greater acknowledgment. Comparable milestones encompass the evolution from scrolls to codices, the 13th-century debut of the compact Paris Bible, the advent of chapter and verse divisions, Reformation-era introductory texts, and the 18th-century acknowledgment of prophetic books as Hebrew verse. “The Bible has never remained static,” MacDonald affirms. “It continually evolves.”

Biblical Cartography’s Influence on Contemporary Borders

Medieval renditions of Holy Land tribal allotments symbolized spiritual legacies for Christians. By the late 15th century, however, these demarcations from biblical maps permeated broader world maps, evolving into representations of political frontiers. Concurrently, fresh political authority paradigms were retroactively applied to scriptural interpretations.

“Maps outlining the twelve tribes’ domains acted as potent catalysts in disseminating these concepts,” MacDonald asserts. “A scripture not originally concerned with modern-style political limits became emblematic of divine orchestration of the world via nation-states.”

“Cartographic lines transitioned from denoting infinite divine covenants to signifying political sovereignty constraints. This shift redefined understandings of biblical geographic depictions.”

“Early modern nation concepts drew from biblical sources, yet sacred text interpretations were reciprocally molded by contemporaneous political theories. The Bible served dually as change instigator and subject.”

Enduring Relevance of These Cartographic Legacies

“For countless individuals, the Bible endures as a foundational reference for convictions regarding nation-states and borders,” MacDonald remarks. “They perceive these notions as scripturally sanctioned, hence inherently valid and just.”

MacDonald references a recent US Customs and Border Protection video wherein an agent invokes Isaiah 6:8—’Then I heard the voice of the Lord saying, “Whom shall I send? And who will go for us?”‘—while helicoptering over the US-Mexico frontier.

Professor MacDonald expresses apprehension that numerous people persist in viewing modern borders as explicitly scriptural. “When querying ChatGPT and Google Gemini on whether borders derive from the Bible, both affirmatively responded ‘yes.’ The truth proves far more nuanced,” he notes.

“We ought to scrutinize any assertion that a societal organization bears divine endorsement, as such claims frequently oversimplify and distort ancient scriptures rooted in distinct ideological and political milieus.”